From a Hammer to a Toolbox: The Health Industry and Systems Thinking_

Those of us who work in healthcare know that health goes beyond having hospitals and operating rooms, beyond having access to drugs and doctors, beyond breathing clean air and eating healthy. Health also depends on the community we live in, our ideas, our culture, and the way we view life in all its spheres. The health of a person or a community depends on the health of other systems: economic, environmental and even political.

It is not easy to be fully convinced that health goes beyond the correct functioning of our biochemistry, but once we are sure about this, we begin to be more proactive in finding ways to act in alignment with the fact that Health is many things at the same time.

There is no doubt that today is the most advanced moment in human history in all areas of knowledge. We know more about chemistry than ever, more about medicine than ever, more about genetics and biology than ever. But in many ways we realize that even with all this knowledge, we are far behind in achieving our full potential in creating true health.

As the American Medical Association (AMA) puts it: “Even if the basic and clinical sciences are expertly learned and executed, without health systems science, physicians cannot realize their full potential on patient’s health or on the population,” (Johnson, 2020, 13; Skochelak, 2017).

The human body is a system that is composed of several physiological subsystems that are interconnected: The respiratory, circulatory, neurological, endocrine and musculoskeletal systems communicate with each other and are interdependent. This system of the human body is, in turn, part of a larger social and cultural system made up of the family, the community and the country in which it lives. In the same way, this societalsystem is part of the natural ecosystem in which it is immersed.

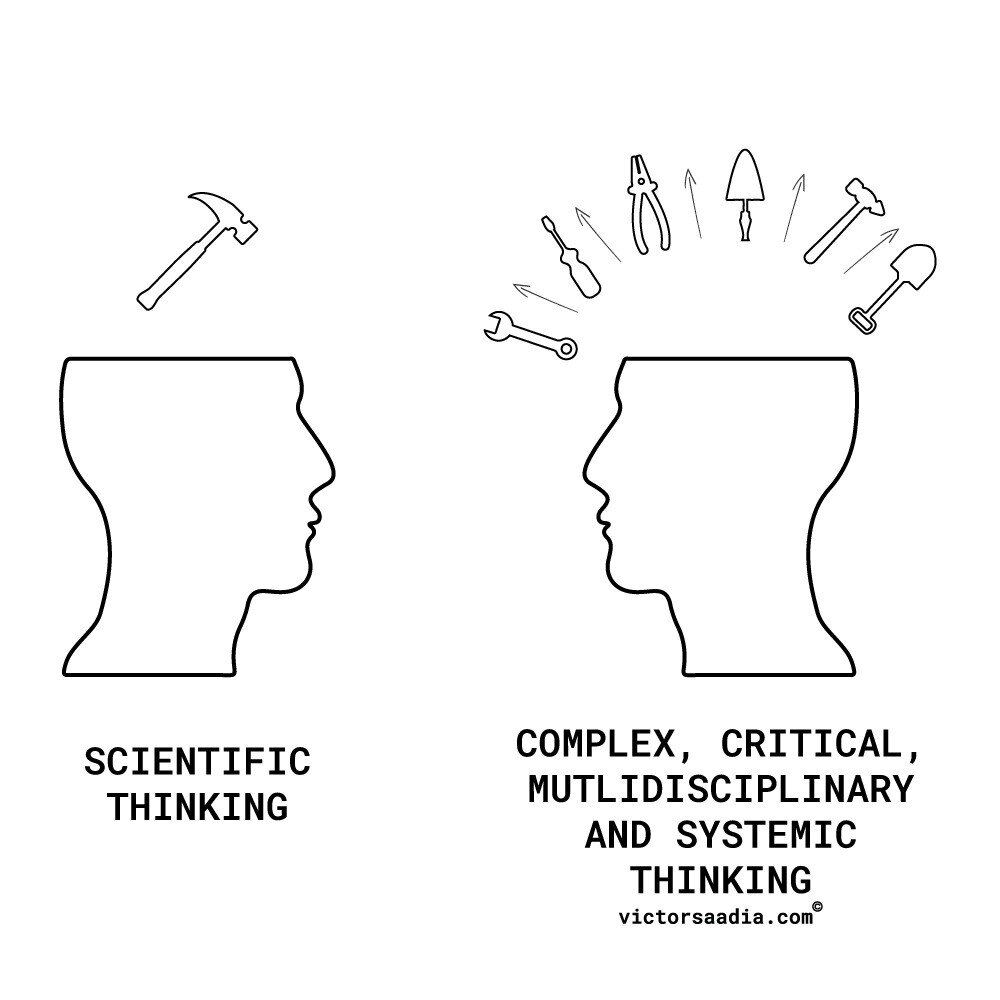

The Hammer: Reductionist Thinking

Our academic upbringing continues to be a reductionist and separatist way of thinking that tries to break up the areas of knowledge into small parts to make it more manageable and understandable. Science, as a methodology, has been very powerful in creating modernity, technology, and the great advances of civilizations. But, at the same time, this linear and one-dimensional way of thinking has created superstructures that have never lost their interdependence, although we have not been trained to understand the deep interrelationships that abound all around.

Linear thinking in health has brought great advances but also great problems. While dozens of statistics are encouraging (with the sustained increase in life expectancy being the most important example), there are also dozens of statistics that show that health problems are worse than ever (such as the epidemic of chronic diseases and its astronomical human and economic costs, or the increasing levels of anxiety and depression in populations, among others).

Reductionist thinking (a term that I do not use in a pejorative way), has made us think that the human being — the individual — is separate from the environment, from his community, from the cultural conditions in which he lives. Therefore, your health — or rather your “absence of disease” as many of us understand it — will always be managed in a very localized way. And therefore, we will only be able to address the problems for which we already have tools.

This lack of effectiveness is due to the fact that in the traditional reductionist paradigm we conceive that everything works like a machine (for example, like a clock or a motor), and therefore, when something breaks down, all we have to do is look for the part that is failing and replace it with a new one. The problem arises when several people with different tools go find the faulty part, because they won’t agree on which is the truly failing part.

For example, if you are a nutritionist, you will see type 2 diabetes as a nutrition issue only and you will intervene there; If you are a doctor, you may see it as a lack of compliance from the patient to stick to the prescribed drug regimen and that is what you will want to correct; If you are a geneticist, you may see it as a genetic issue; if you are a sociologist you will see it as a matter of culture and ideology; if you work in an NGO you will see it as a conspiracy of the food industry; If you work on public policies, you will see it as a disobedient population issue; if you are a psychologist you will see it as if it was caused by being depressed; if you are an activist you will see it as a social justice issue; And if you are a patient, you probably believe thatdiabetes is your personal fault for not knowing how to eat and not wanting to exercise.

Who is right?

Everyone. Health is many things at the same time.

To use a familiar analogy: if all we have is a hammer, then we will see all problems as a series of nails. I would venture to say, then, that our hammer has been our scientific and reductionist thinking, vastly powerful, but no longer useful with the growing realization that problems are unequivocally interconnected.

Toolbox: Systemic Thinking

The analysis of complexity and systems thinking are new languages (and tools) that are allowing us to broaden our perspectives and get out of reductionisms in order to understand in a more complete (but not total) way the profound interdependence of the systems that make up the health of an individual, a family, a society or the species.

As health service providers, systems thinking challenges us to understand (and act) through the multiple interactions and interdependencies of all the elements and processes that make up what we call health or well-being. This thinking assumes that human behavior, both individual and collective, is not linear but multifactorial and multidimensional.

In fact, as a civilization, we have always thought and acted systemically, but by boasting about ourachievements, we forget to give ourselves credit for doing so. As Bill Gates recently said in reference to systems: “Jonas Salk was an amazing scientist, but he isn’t the only reason we’re on the doorstep of eradicating polio — it’s also thanks to the coordinated vaccination effort by health workers, NGOs, and governments. We miss the progress that’s happening right in front of us when we look for heroes instead of systems. If you want to improve something, look for ways to build better systems,”(Johnson, 2020, viii).

Jonas Salk was a hero, but heroes never act in isolation. And in our quest to have unique heroes to get us out of trouble (a novel drug, an incredible technological advance) we forget that, while heroes are necessary, what is most necessary is to pay attention to the system where these heroes are born and nurtured. Jonas Salk was a hero but so are all the other participants (human, technological and environmental) who allowed his discoveries to happen and spread throughout almost all of humanity.

The hero — who is nothing more than the health professional, the businessman, a Health Ministry — can only become a hero to the extent that they understand that all the ideas, proposals, and actions will only have an impact if they manage to integrate them at various levels and scales with the systems in which they are embedded. In a world of increasing complexity and interdependence, tomorrow’s heroes are the ones who constantly expand their toolbox with more than just a mighty hammer.

In a world where the human race has the ability to create much more information than we can absorb, fostersmore interdependence than we can manage, and accelerates change at a much faster pace than we can keep up with; the hero of tomorrow is the one, who while being armed with a new way of thinking, does not allow himself to succumb to the burden of the complexity of reality. (Johnson, 2020, 6; Senge, 1990)

Nowadays, any health professional, any executive of a health company and any public policy decision-maker, has to be a bit of a doctor, a bit of a psychologist, a sociologist, a communication scientist, an entrepreneur and even a bit of a philosopher to be able to think systemically.

On the business side, it is also clear that private and public health companies, many of them born in an industrial era, are no longer adequate for the complexity of what we understand today as health. Business continues to be disease-driven, the mind-body connection is not addressed, the well-being of health professionals is not seen as fundamental, and organizational hierarchies address the issue of health as a mechanistic and transactional thing.

That is why the World Health Organization itself makes continuous calls to think in a systemic way to approach “problem-solving that views problems as part of a wider dynamic system. Systems thinking involves much more than a reaction to present outcomes or events. It demands deeper understanding of the linkages, relationships, interactions, and behaviors among the elements to characterize the entire system.” (Johnson, 2020, 9; Savigny, 2009)

Of course, there are many barriers to adopting this type of thinking and begin to take action in a more comprehensive way. Some barriers have to do with the constant time pressure in which we live and our willingness to leave our “comfort zone”. But more and more of us are developing new tools to be able to take the next step in a more strategic, future-focused, human-centered, and much more systemic way than we have allowed ourselves to do so far.

Systems thinking evolves our mechanical dimension into a human dimension (and we use this word because, luckily, “human” is still something that we allow ourselves to constantly redefine). This entails an unavoidable discomfort (if only because we are changing our way of thinking and acting!), but that is why we have to find a way so that systems thinking also feels somewhat safe, so that we dare to be more creative and disruptive in the creation of new virtuous spirals of growth, collaboration, and, yes, health.